We live in a time when public discourse is louder, faster, and more emotionally charged than ever before. But with that urgency comes a quiet danger — not just misinformation, but manipulation. Not just bad arguments, but dishonest framing. And one of the most insidious forms of rhetorical sleight-of-hand is something few people know by name, but most have experienced firsthand:

The Motte & Bailey fallacy.

It’s not new. It’s not exclusive to any side of the political spectrum. And chances are, you’ve been on both the receiving and the giving end of it — even if unintentionally. It’s what happens when someone retreats to a safe, agreeable position (the motte) when challenged, but then returns to aggressively defend or imply a much more extreme and controversial claim (the bailey) when unopposed.

It’s a tactic of evasion and exploitation. It distorts meaningful dialogue. It shifts burden without accountability. And worst of all? It feels persuasive — even as it erodes truth.

This article isn’t just a breakdown of what the Motte & Bailey fallacy is. It’s a guide to recognizing it, resisting it, and refusing to use it — whether in politics, media, activism, social media debates, or personal conversations.

Because if we want honesty in our culture, it starts with integrity in our arguments.

Let’s unpack the problem.

What Is the Motte & Bailey Fallacy?

At its core, the Motte & Bailey fallacy is a bait-and-switch tactic — a way to promote extreme or controversial views while hiding behind safer, more socially acceptable ones when challenged.

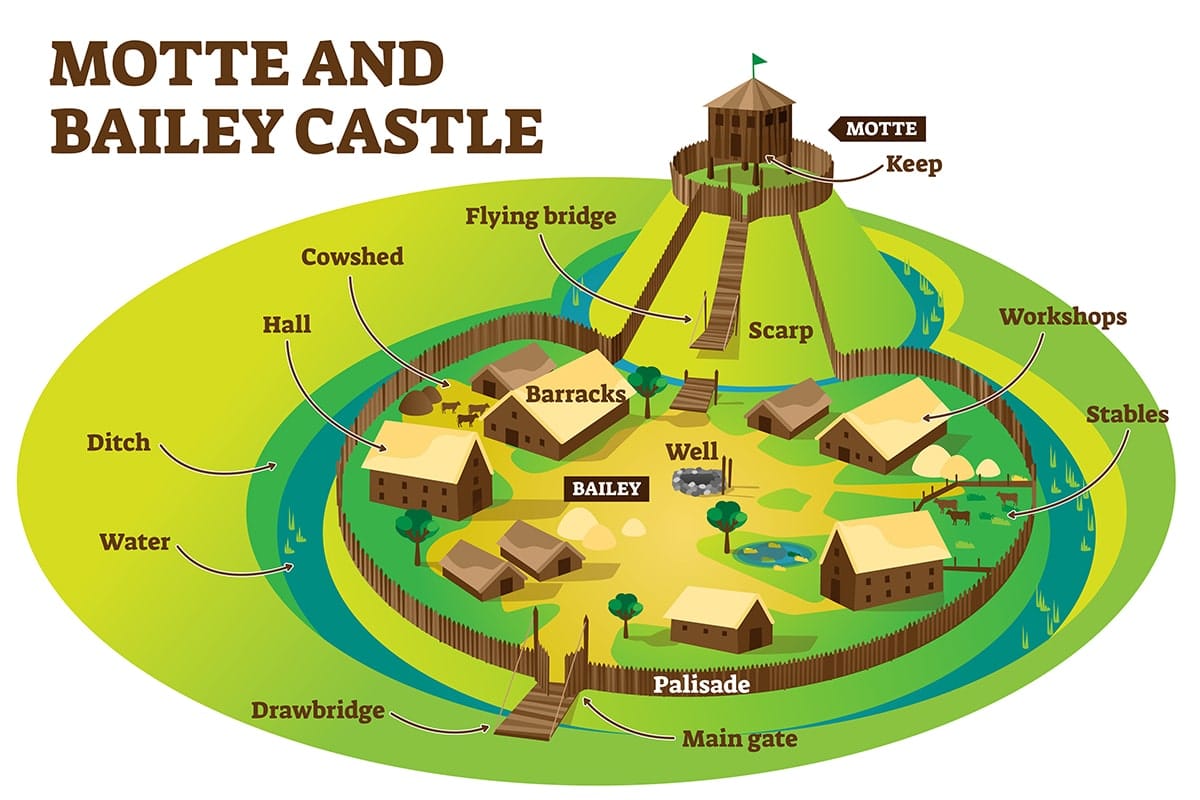

The term was coined by philosopher Nicholas Shackel in 2005, drawing from medieval fortification structures. Picture this: a bailey is a large, open courtyard — fertile and expansive, but vulnerable to attack. A motte, on the other hand, is a small, fortified hilltop keep — difficult to assault, but too cramped to comfortably live in.

In debate, the bailey is the bold, often radical claim — the one someone might post on social media, shout at a protest, or weave into ideological frameworks. It’s attention-grabbing and emotionally provocative. But when this position is challenged, suddenly, the speaker retreats to the motte — a much tamer, more defensible statement that no reasonable person would argue against.

And once the heat dies down? They sneak back into the bailey, often without ever addressing the original criticism.

A Simple Breakdown:

- The Bailey: Bold, ideological, controversial claim

- The Motte: Safer, widely acceptable, watered-down version

- The Tactic: Use the bailey to spread influence, use the motte to dodge critique

This isn’t just a flaw in logic. It’s a deliberate obfuscation of intent. It creates a rigged battlefield where the rules of engagement shift mid-debate — leaving opponents frustrated, cornered, or accused of “not listening.”

Let’s see how this works in practice.

Step 1: Promote the Bailey

The speaker starts with a bold, provocative claim — the one that generates attention, rallies support, or stirs emotion. This is the bailey: dramatic, ideological, and often overstated. It might sound revolutionary, but it’s also vulnerable to legitimate criticism.

Step 2: Retreat to the Motte

When someone challenges the bailey — with facts, questions, or counterpoints — the speaker quickly retreats to the motte: a tamer, watered-down version of the same idea. The motte is intentionally vague, seemingly reasonable, and difficult to argue against.

Step 3: Return to the Bailey (Until Challenged Again)

Once the criticism has passed or the audience forgets the distinction, the speaker returns to promoting the bailey — either directly or by implication — without ever having to defend it honestly. And the cycle repeats.

Real-World Examples

Let’s ground this with actual examples from politics, activism, and online discourse.

Example 1: Ideological Claim

- Bailey: “All property is theft.”

- Motte: “We should examine the moral issues around wealth inequality.”

💡 Why it works: The bailey grabs attention — it’s radical and disruptive. But when someone points out that, say, farmers or renters also have property rights, the arguer falls back on a safer critique of economic imbalance. Once the pushback ends, they often go right back to the original anarchist framing.

Example 2: Political Policy

- Bailey: “We should abolish the police.”

- Motte: “We need to invest more in community services and mental health support.”

💡 Why it works: Few people would argue against better funding for social services. But if the original demand was to completely eliminate law enforcement, it’s intellectually dishonest to hide behind a reformist message when challenged.

Example 3: Social Theory

- Bailey: “Speech is violence.”

- Motte: “Words can be deeply hurtful and emotionally damaging.”

💡 Why it works: Everyone agrees that language can cause harm. But the bailey jumps to an extreme equation — legally or morally equating speech with physical assault. When questioned, the speaker retreats to the motte, but continues pushing for policies that treat disagreement as violence.

Example 4: Environmental Policy

- Bailey: “Humanity should stop having children to save the planet.”

- Motte: “We should be more mindful about overpopulation and resource use.”

💡 Why it works: The bailey is extreme and controversial. But if someone points out ethical concerns or demographic decline, the speaker sidesteps and says they “just meant” we should consider sustainability — then goes back to promoting anti-natalist rhetoric elsewhere.

This tactic isn’t just frustrating — it actively prevents productive conversation. Because the person deploying it isn’t interested in clarity or accountability. They’re interested in winning, or influencing, without being pinned down.

And that’s what makes it so dangerous.

Why It’s So Effective — and So Dangerous

The Motte & Bailey tactic works because it exploits how people process complexity. It plays on the human instinct to avoid conflict, to grant the benefit of the doubt, and to assume good faith in others. Most people don’t want to seem unfair, uncharitable, or aggressive — especially in public discourse. And that’s exactly where the fallacy gets its strength.

When someone retreats to a milder claim, most of us back off. We don’t want to be accused of misunderstanding. We don’t want to “punch down” on someone simply stating a seemingly benign idea. But that’s the trick: they weren’t just saying the benign thing. They were pushing the more radical one all along — until it became inconvenient.

This tactic allows someone to:

- Promote a controversial or extreme belief without taking full accountability for it.

- Appear more reasonable than they really are, especially to casual observers.

- Dismiss critics as reactionary or misinformed when the true disagreement lies with the Bailey, not the Motte.

It becomes incredibly difficult to debate honestly when your opponent is constantly shifting terrain. One moment, you’re engaging a radical claim. The next, they’re acting like you’re attacking a totally normal and widely accepted principle. And once the scrutiny fades, they quietly go back to the extreme position — often doubling down, emboldened by your silence.

This isn’t just frustrating. It’s corrosive. It distorts what the conversation is even about. It rewards rhetorical slipperiness over clarity. And worst of all? It trains people to manipulate discourse, rather than participate in it.

When we let the Motte & Bailey go unchallenged, we don’t just lose the debate — we lose the possibility of honest dialogue.

How to Spot the Motte & Bailey in the Wild

The Motte & Bailey fallacy isn’t always easy to identify — especially in real-time conversation. It’s subtle, it’s slippery, and it often hides beneath good intentions. But once you learn the signs, you’ll start noticing it everywhere.

Here are some common red flags to watch for:

1. The Sudden Retreat

A bold claim is made — something controversial, aggressive, or ideologically loaded. But when questioned, the speaker immediately pivots to a much softer, more agreeable position. The shift often happens so fast it’s hard to pin down.

Example:

- Original: “The justice system is inherently racist and must be dismantled.”

- Retreat: “I’m just saying we should be aware of bias and push for reform.”

2. Accusations of Straw-manning

When a critic directly addresses the more extreme claim (the bailey), the speaker responds by accusing them of attacking a position they never held — even though they did, just moments earlier.

Watch for:

“That’s not what I meant. You’re twisting my words.”

“No one is actually saying that.”

Except… they were. You heard it. You read it. You’re not crazy.

3. Repetition Without Clarification

After defending only the motte, the person later continues repeating the bailey — as if the prior challenge never happened. They alternate between defensible and indefensible claims depending on the audience or mood.

Pattern:

Claim → Pushback → Retreat → Wait → Repeat.

This cycle lets them enjoy the influence of a radical idea without the responsibility of defending it.

How to Avoid Using the Motte & Bailey Yourself

It’s easy to criticize others for intellectual dishonesty. It’s much harder to recognize when we’re the ones doing it — especially when we believe deeply in our position. But if we want to elevate the quality of discourse — in politics, in media, in everyday conversation — we have to start with ourselves.

Here’s how to avoid falling into the Motte & Bailey trap:

1. Be Clear About What You Mean

Before you share a claim, ask yourself: Do I believe this strongly? Would I defend it under scrutiny?

If you wouldn’t — clarify or reframe before you post, speak, or debate.

Avoid vague generalizations like:

“Capitalism is evil.”

“All cops are bad.”

“Religion is a scam.”

Unless you’re ready to define those terms and engage with what they really mean.

2. Stick to One Claim at a Time

If you’re challenged, don’t dodge the issue by softening your argument unless you’re actually revising your position.

Shifting from “abolish prisons” to “reform sentencing for non-violent offenders” mid-discussion might feel like clever maneuvering — but it’s rhetorical sleight-of-hand.

If your view evolves in real-time (which is a good thing!), just say so:

“You’re right — I think I overstated my original point. What I actually mean is…”

That’s not weakness. That’s integrity.

3. Separate Belief From Strategy

Sometimes people use extreme claims not because they believe them fully, but to provoke discussion or draw attention. That’s manipulative — and it damages your credibility.

If you’re using shock to spark dialogue, say so upfront:

“This is intentionally provocative — let’s break it down.”

4. Don’t Hide Behind the Motte

If you truly believe in the bailey, defend it with substance. If you don’t — let it go. Don’t use the motte as a shield to avoid discomfort, accountability, or dissent.

Remember: You can’t have it both ways. If you want to be taken seriously, you have to choose what hill you’re standing on — and stay there long enough to have a real conversation.

What to Do When You Encounter the Motte & Bailey Fallacy

Spotting a Motte & Bailey in the wild is one thing. Calling it out — without derailing the conversation or sounding combative — is another. Here’s how to do it with clarity and integrity:

1. Anchor the Conversation

If someone makes a bold claim (the bailey), and then retreats, politely guide them back to it.

“Just to clarify — are you saying [extreme claim], or [milder claim]? I want to make sure we’re discussing the same thing.”

This forces clarity. It’s hard to play both sides when the spotlight is on the fork in the road.

2. Ask Them to Choose

Don’t let someone toggle between the motte and bailey without accountability. Ask:

“Which position are you actually defending here?”

If they say both — press further. “Would you be willing to defend both under scrutiny, or is one just a rhetorical tool?”

3. Refuse to Debate the Motte if the Bailey Was the Original Claim

If the conversation started around abolishing police, don’t let it get watered down into “we should invest in mental health” without noting the shift.

You can say:

“I’m happy to discuss community investment, but that’s not what was originally being proposed. Are we switching topics, or walking back the claim?”

4. Use Humility — But Be Direct

This isn’t about “owning” the other person. It’s about clarity. Stay calm. Ask questions. Maintain a tone that invites honesty, not defensiveness.

“I don’t think you’re being dishonest — I just want to understand your actual position so we’re not talking past each other.”

5. Encourage Better Debate Culture

Sometimes, people fall into this fallacy because they don’t feel safe holding complex beliefs. If they feel attacked, they’ll retreat — even if their bailey is sincere.

Create space by saying:

“It’s totally fair to explore bold ideas — as long as we’re clear about what we’re saying and what we’re not.”

Final Thoughts: Integrity Over Influence

The Motte & Bailey fallacy isn’t just a debate trick — it’s a reflection of how easily we can be seduced by persuasion over principle. In a culture drowning in half-truths, tribalism, and performance-based discourse, it’s more important than ever to value clarity over cleverness, and honesty over rhetorical advantage.

When we dodge accountability for our real beliefs — or let others do the same — we don’t just weaken our arguments. We weaken trust, truth, and the possibility of meaningful progress.

If we want to live in a society where ideas can be exchanged with good faith, where people are taken seriously, and where dialogue leads to understanding (not just influence), then we must reject the Motte & Bailey — in others, and in ourselves.

Call it what it is.

Challenge it.

And most importantly: don’t use it.

Because integrity doesn’t just win debates — it builds something worth debating for.

Watch This Fallacy in Action

To see how the Motte & Bailey fallacy can play out in real time — especially when exposed — watch this bold and unfiltered example: