Why Canadians must demand action before more money gets spent abroad

Canada is a wealthy, advanced nation—yet dozens of First Nations communities still lack access to safe drinking water. As of mid‑2025, nearly 50 reserves remain under long‑term drinking water advisories. Many have waited 10–30 years, despite billions allocated. Meanwhile, aside from NATO defense spending, billions more continue going toward military aid and foreign commitments.

It’s time Canadians asked:

Should we fix what’s broken at home before exporting taxpayer dollars abroad?

The Communities Left Behind

Imagine waking up every day in one of the wealthiest countries in the world — and still being told not to drink the water. Not for a week. Not for a month. But for years. In some cases, for decades.

This is the lived reality for thousands of people across Canada. Entire communities — families, children, Elders — have spent 10, 20, even 30+ years under boil water advisories. Water that comes from the tap must be boiled to drink. Sometimes it’s brown. Sometimes it smells. Sometimes it’s not safe to bathe in. In many cases, it’s completely unavailable due to broken infrastructure or underfunded treatment plants.

This isn’t happening in a remote desert or a war-torn country.

This is happening in Canada. Right now.

And yet, while billions are spent on foreign aid and military operations abroad, these communities wait. Wait for funding. Wait for construction. Wait for political will. Wait for justice.

The table below outlines just a portion of these communities — a list of just 50 First Nations (of which there are many more) — all but one still affected by long-term drinking water advisories as of mid-2025. For each, you’ll see when the issue began, how many people are impacted, what it might cost to fix, and how long it would actually take — if governments treated it like a priority.

Let these numbers sink in. Then ask yourself:

Why are these people still waiting?

| Community | Province | Advisory Since | Population Affected | Est. Fix Cost | Est. Fix Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neskantaga FN | ON | 1995 | ~244 | $25–35 M | 3–4 yrs |

| Kashechewan FN | ON | 2005+ | ~1,900 | $200 M | 10+ yrs |

| Pikangikum FN | ON | 2010s | ~2,334 | $60 M | Several yrs |

| Shoal Lake 40 FN | MB/ON | 1997–2021 | ~1,000+ | $33 M | Achieved (2019‑21) |

| Mohawks of Bay of Quinte FN | ON | 2008 | ~5,600 | $18.2 M | Multi-phase |

| Mishkeegogamang FN | ON | May 2025 | 95 homes + 20 bldgs | $2–4 M | 3–4 yrs |

| Weenusk FN | ON | May 2025 | 93 homes + 5 bldgs | $2–4 M | 3–4 yrs |

| Berens River FN | MB | May 2025 | 350 homes + 4 bldgs | $4–6 M | 3–4 yrs |

| Ḵwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis FN | BC | ~2016 | 26–50 | $1–2 M | ~3 yrs |

| Eabametoong FN | ON | 2000s | ~977 | $8–12 M | 3–4 years |

| Cat Lake FN | ON | 2010s | ~700 | $5–7 M | 3–4 years |

| Gull Bay (Kiashke Zaaging) | ON | 2010s | ~600 | $5–7 M | 3–4 years |

| Deer Lake FN | ON | 2010s | ~200–300 | $3–5 M | 2–3 years |

| North Spirit Lake FN | ON | 2010s | ~~900 | $7–10 M | 3–4 years |

| Muskrat Dam Lake FN | ON | 2010s | ~~400 | $4–6 M | 3–4 years |

| Rainy River FN | ON | 2010s | ~~400 | $4–6 M | 3–4 years |

| Sandy Lake FN | ON | 2010s | ~~2,300 | $15–20 M | 4–5 years |

| Slate Falls Nation | ON | 2010s | ~~400 | $4–6 M | 3–4 years |

| Bearskin Lake FN | ON | 2010s | ~~600 | $5–7 M | 3–4 years |

| Little Pine FN | SK | 2010s | 800–1,200 | $8–12 M | 3–4 years |

| Okanese FN | SK | 2010s | 400–600 | $5–7 M | 3–4 years |

| Peepeekisis Cree Nation No.81 | SK | 2010s | 600–900 | $6–8 M | 3–4 years |

| Mathias Colomb FN | MB | 2010s | ~1,400 | $15–20 M | 4–5 years |

| Shamattawa FN | MB | 2010s | ~1,300 | $14–18 M | 4–5 years |

| Tataskweyak Cree Nation | MB | 2010s | ~1,600 | $18–22 M | 4–6 years |

| Tootinaowaziibeeng Treaty Reserve | MB | 2010s | ~1,200 | $12–16 M | 4–5 years |

| Waywayseecappo FN | MB | 2010s | ~1,600 | $18–22 M | 4–5 years |

| Miawpukek FN | NL | 2010s | ~1,000 | $10–14 M | 3–4 years |

| Mishkeegogamang FN (dup) | ON | 2025 | ~95 homes + 20 buildings | $2–4 M | 3–4 years |

| Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte | ON | 2008 | ~5,600 | $18 M | 3–5 yrs |

| Pikangikum FN | ON | 2010s | ~2,334 | $60 M | Several years |

| Sapotaweyak Cree Nation | MB | Prior to 2021 | ~1,900 | $14.2 M | 2–3 yrs |

| Cheslatta Carrier Nation | BC | 2006+ | ~330 | MultiM | ~1 yr |

| Semiahmoo FN | BC | ~2006 | ~98 | $1–3 M | 2–3 yrs |

| Little Pine FN (dup) | SK | 2010s | 800–1,200 | $8–12 M | 3–4 yrs |

| Okanese FN (dup) | SK | 2010s | 400–600 | $5–7 M | 3–4 yrs |

| Peepeekisis Cree Nation (dup) | SK | 2010s | 600–900 | $6–8 M | 3–4 yrs |

| Mathias Colomb FN (dup) | MB | 2010s | ~1,400 | $15–20 M | 4–5 yrs |

| Shamattawa FN (dup) | MB | 2010s | ~1,300 | $14–18 M | 4–5 yrs |

| Anishnaabeg of Naongashiing | ON | 2010s | ~200–300 | $3–5 M | 2–3 years |

| Chippewas of Georgina Island | ON | 2010s | ~500 | $6–8 M | 3–4 years |

| Chippewas of Nawash FN | ON | 2010s | ~2,800 | $30–40 M | 4–6 years |

| Chippewas of the Thames | ON | 2022 | ~2,800 | $25–35 M | 3–5 years |

| Eabametoong FN (dup) | ON | 2000 | ~977 | $8–12 M | 3–4 years |

| Gull Bay (dup) | ON | 2010s | ~600 | $5–7 M | 3–4 years |

| Lac La Croix FN | ON | 2010s | ~500 | $5–7 M | 3–4 years |

| Marten Falls FN | ON | 2010s | ~850 | $10–14 M | 3–4 years |

| MunseeDelaware Nation | ON | 2010s | ~250 | $4–6 M | 2–3 years |

| Nibinamik FN | ON | 2010s | ~400 | $5–7 M | 3–4 years |

| Wawakapewin FN | ON | 2010s | ~100–150 | $2–4 M | 3–4 years |

Why Don’t First Nations Just Fix It Themselves?

One of the most common knee-jerk reactions to the water crisis is:

“The government gives billions to First Nations. Why don’t they use that money to fix their water systems?”

It’s a fair question — but it misses several important realities.

1. Federal Funding Is Earmarked, Not Flexible

Most money sent to First Nations communities comes in the form of restricted funding agreements. That means the money must be used for very specific purposes: education, housing, social services, health, etc. It often cannot legally be reallocated to build water infrastructure — even if clean water is the more urgent need.

These funds are also highly conditional and subject to year-end clawbacks if unspent. That means if a community doesn’t use the money fast enough (or exactly how Ottawa dictates), it’s pulled back. There is no savings account. There is no rainy-day fund.

2. Water Systems Are Under Federal Jurisdiction

Unlike municipalities that manage their own utilities, most First Nations don’t control their water infrastructure. Instead, these systems fall under federal responsibility, making Ottawa the owner, operator, and funder of record. It’s not just a matter of money — it’s a matter of legal jurisdiction.

Communities are often caught in bureaucratic limbo: if they try to build or upgrade water systems independently, they still have to go through federal approvals, assessments, and engineering specs that can take years to clear.

3. Underfunded by Design

Numerous reports — including by the Parliamentary Budget Officer and Auditor General of Canada — have confirmed what many Indigenous leaders have said for decades:

Federal infrastructure funding for reserves is chronically underfunded and structurally broken.

In fact, a 2011 assessment estimated the cost to bring all First Nations water systems up to standard at $3.2 billion — but only a fraction of that was committed until very recently. Even today, many “completed” projects lack long-term operation and maintenance funding, meaning the plants fail within a few years due to breakdown or lack of trained staff.

4. Blaming First Nations Is a Deflection

The narrative that “First Nations mismanage money” has long been used as a deflection — ignoring the complex reality of decades of colonial policy, restrictive funding, and federal neglect.

In truth, many Indigenous communities are doing extraordinary work with limited resources — and often stretching dollars far further than most municipalities would ever attempt. But asking them to solve a crisis that was caused and maintained by federal policy is not only unfair — it’s structurally impossible without government partnership.

This isn’t a handout.

This is a matter of treaty obligation, legal responsibility, and basic human dignity.

First Nations can’t just fix it themselves because they weren’t given the tools — or the authority — to do so. And until that changes, it is up to Canada as a whole to fix what it broke, and finally provide what it promised.

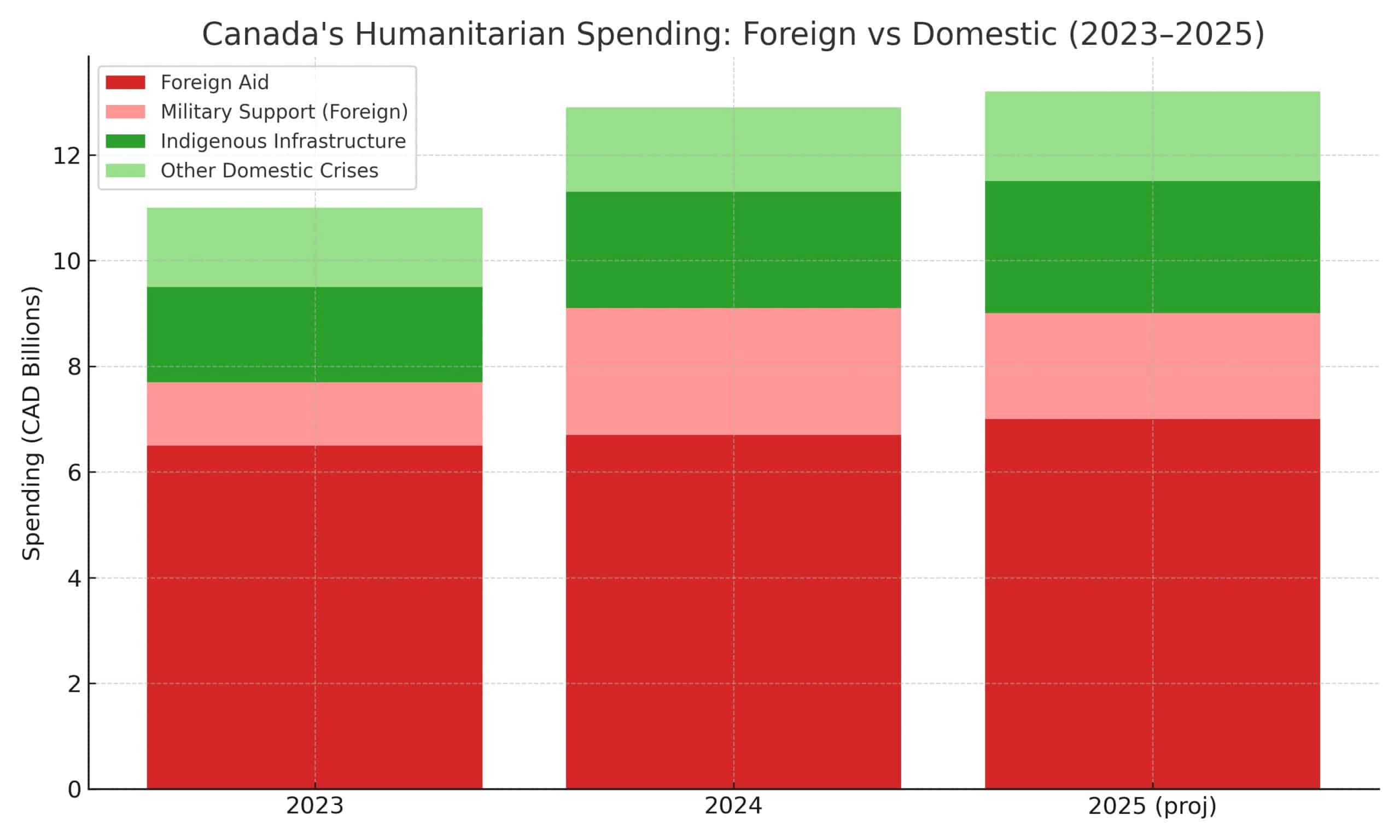

Where Else Do Taxpayer Dollars Go?

As nearly 50 First Nations communities live under long-term boil-water advisories — some for over three decades — billions of Canadian taxpayer dollars are being allocated to causes, conflicts, and investments far from home.

Many of these expenditures may appear noble or strategic on the surface. But when you compare them to the solvable crisis of clean water in Indigenous communities, the disconnect becomes glaring.

Here’s where some of that money is going:

1. Military and Economic Aid to Ukraine (Non-NATO Commitment)

-

Since 2022, Canada has committed over $4.5 billion in aid to Ukraine, including:

-

$2.4 billion in direct military assistance

-

Tanks, drones, air defense systems, artillery, ammunition

-

$1.5 billion in direct loans and financial support

-

Humanitarian aid, reconstruction funds, and development support

-

-

In June 2025, Canada pledged an additional $2 billion, bringing the total close to $6.5 billion and extending commitments through 2029.

That’s more than double what’s estimated to end all First Nations boil-water advisories, train operators, and maintain clean systems long-term.

2. Foreign Aid & Development Spending

Canada’s annual foreign aid budget consistently hovers around $6.5 billion per year, and while much of this goes toward global health and education, some notable projects include:

-

$200 million to support gender-focused entrepreneurship programs in Africa

-

$125 million toward carbon emissions projects in Southeast Asia

-

$150 million to promote media literacy and civil society in Eastern Europe

These are commendable causes — but they’re fully funded while basic water access remains unfunded here at home.

The Shift: When Did Dandelions Become “Weeds”?

3. UN Peacekeeping & Global Engagement

Canada contributes hundreds of millions each year to:

-

United Nations Peacekeeping forces

-

Overseas embassy expansions and security details

-

Funding NGOs and think tanks operating in regions like Syria, Sudan, and Haiti

In contrast, a single community like Neskantaga First Nation has waited 30 years for clean water — often relying on bottled shipments and temporary repairs.

4. Administrative Bloat & Unused Allocations

In 2023, the Parliamentary Budget Officer reported that:

-

Over $38 billion in approved federal funds went unspent

-

Delays in infrastructure, health, and Indigenous services were among the worst-hit

This means money meant to fix problems already approved by Parliament — including clean water — was never delivered.

Instead of reallocated, these funds were rolled over or vanished into federal backlogs and bureaucracy.

5. Space Programs and International R&D

-

In 2024, Canada committed:

-

$1.2 billion toward a moon exploration partnership with NASA

-

$525 million to international AI and tech research hubs

-

$210 million toward global digital infrastructure partnerships

-

All while dozens of Indigenous children grow up unable to safely bathe, brush their teeth, or drink water from the tap.

The Prioritization Problem

None of these expenditures are inherently wrong.

But the issue is priority.

How can a country justify exploring the moon or expanding diplomatic networks when children within its own borders have never known clean water at home? How can Canada lead on global health when its own citizens are boiling brown water to survive?

Why This Matters

It’s easy to read statistics — years under advisories, millions affected — and become desensitized. But we must resist that impulse. Because this isn’t just a data problem. It’s a human problem. A justice problem. A Canadian problem.

Water Is Not a Luxury. It Is a Right.

Water is the foundation of life. Access to clean, safe drinking water is not just a “nice-to-have” — it’s a fundamental human right, recognized by the United Nations and enshrined in Canada’s commitments to international law. Yet in our own country, there are children who have never brushed their teeth from a tap. Elders who boil brown water to cook. Parents who must rely on weekly deliveries of bottled water just to keep their families safe.

What’s more, these are not isolated incidents. This is not about remote geography or logistical inconvenience. These are the direct results of chronic underinvestment, bureaucratic inaction, and colonial policies that continue to affect Indigenous Peoples today.

We Can Afford to Fix This — We Just Haven’t Prioritized It

Canada is not a country without means. We’re one of the richest nations on Earth, with a GDP over $2 trillion and billions in annual discretionary spending. We fund moon missions, international military deployments, and foreign infrastructure projects.

And yet, while billions are earmarked for foreign causes — many of them important — communities right here at home go decades without potable water. Some communities, like Neskantaga, have been under a boil-water advisory for over 30 years.

Let that sink in: there are adults in this country who have lived their entire lives without safe water. That isn’t an infrastructure issue. That’s a national disgrace.

The Cost of Inaction is Higher Than You Think

Every year this crisis continues, the toll rises:

-

Emergency bottled water shipments cost millions.

-

Medical conditions linked to unsafe water — like chronic skin infections, stomach illness, and waterborne diseases — burden healthcare systems and shorten lives.

-

Community evacuations due to infrastructure failure cost hundreds of thousands.

-

Social despair, mistrust in government, and trauma deepen.

Meanwhile, the actual cost to resolve this — based on federal audits and engineering assessments — remains a fraction of what’s spent overseas or lost to inefficiency every year.

This Is About Justice — Not Charity

Indigenous communities are not asking for favors. They’re asking for what was promised.

Clean water is not a gift. It’s a responsibility enshrined in treaties, affirmed in Canadian court rulings, and guaranteed under Section 36 of the Constitution Act, which promises “essential public services of reasonable quality to all Canadians.”

That includes the original Peoples of this land. And until Canada treats its own citizens — especially its First Peoples — with the dignity and care it extends to foreign interests, it will continue to fail its most basic measure of success: how it cares for its most vulnerable.

You may not live in one of these communities.

You may never have gone a day without clean water.

But as a Canadian, this is your story too.

Because we are only as strong as the country we build together. And right now, that country has cracks in its foundation — literal and moral.

Fixing this isn’t just the right thing to do — it’s the smart thing to do. The fair thing. The Canadian thing.

Let’s not be remembered as the generation that knew and did nothing.

Let’s be the ones who finally said: Enough.