Context: Why This Is Coming Up (Again)

Following the 2025 federal election and Mark Carney’s Liberal Party win, Alberta has once again found itself in the familiar position of frustration, feeling ignored by a national political system that doesn’t seem to reflect its values or priorities.

In that frustration, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith has revived the rhetoric of provincial separation — even suggesting the possibility of a referendum on leaving Canada.

It’s easy to see why this strikes a chord.

A sense of alienation. A desire for autonomy. A need to feel heard.

But regardless of how justifiable the frustration may be, the question of separation isn’t just emotional. It’s legal. Historical. Constitutional. And deeply intertwined with Indigenous rights and treaty obligations that predate Alberta’s existence as a province.

One of the most important — and misunderstood — pieces of the Alberta separation debate is this:

Alberta didn’t join Confederation. It was created by it.

That may sound like a technical detail. But in constitutional terms, it’s everything.

The Land Before Alberta: Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory

Before Alberta existed as a province, the land it now occupies was part of a much larger region known as Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory. These weren’t provinces. They weren’t colonies. They were massive, loosely governed fur-trading territories controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) under a royal charter granted in 1670 by King Charles II.

That charter gave HBC near-complete control over trade, governance, and land rights in a region that spanned a huge portion of what’s now central and western Canada.

So while provinces like Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, and Ontario developed out of British colonial structures — with some form of government, law, and negotiated entry into Confederation — Alberta did not.

1870: The Land Is Surrendered to Canada

In 1869, the Canadian government negotiated a deal to acquire Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company.

-

The deal became official in 1870, when Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory were formally transferred to Canada by deed of surrender.

-

In return, HBC received:

-

£300,000 (about $1.5 million at the time)

-

The right to retain trading posts and certain land blocks

-

A legacy of future legal fights over who actually held title to the land (hint: it wasn’t HBC to begin with — it was Indigenous territory)

-

From this point on, the entire region — including what would become Alberta — became federal territory, directly governed by Ottawa.

1905: The Alberta Act and Saskatchewan Act

On September 1, 1905, the Parliament of Canada passed the Alberta Act and Saskatchewan Act, officially carving out two new provinces from what had previously been part of the North-West Territories.

These were federal creations, passed by statute — not treaties. Not negotiations. Not mutual agreements.

Key points:

-

Alberta didn’t exist as a legal entity before this.

-

It had no pre-existing legislature, governance structure, or colonial government.

-

Its boundaries, institutions, and powers were all determined by the federal government under the Constitution.

This is very different from how most other provinces came into being.

Constitutional Consequences

Because Alberta was created by federal statute, it:

-

Never negotiated its way into Confederation

-

Didn’t exist as a legal or political entity before 1905

-

Received its powers and rights from the federal government, not through bilateral agreements

This makes Alberta constitutionally different from provinces like Quebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and even British Columbia, which joined Confederation through negotiated terms of union or special acts that formalized their entry.

In legal terms, Alberta is a creature of federal law — not an equal founding partner in the federation.

And that matters. A lot.

Because when we talk about a province leaving Confederation, we have to ask:

Can something that was never sovereign to begin with, legally become sovereign on its own?

In Alberta’s case, the legal answer — as confirmed by constitutional scholars and the Supreme Court of Canada — is no. Not unilaterally. Not without national consensus. And certainly not without dealing with Indigenous treaty rights (more on that later).

Referendums: Expression, Not Exit

What a vote can (and can’t) do when it comes to provincial separation

Whenever talk of provincial secession flares up — as it has recently with Alberta Premier Danielle Smith’s suggestion of a referendum — one question tends to dominate the headlines:

“Can a province vote to leave Canada?”

The short answer is: no, not unilaterally.

A referendum in Alberta may express frustration. It may signal political will. It may even spark national headlines.

But a referendum alone has no legal power to separate Alberta from Canada — and that’s not opinion. That’s constitutional law.

Let’s unpack why.

What the Supreme Court Actually Said (Hint: This Isn’t Guesswork)

In 1998, the Supreme Court of Canada was asked to rule on whether Quebec could legally secede from Canada following a referendum.

In its landmark Secession Reference, the court ruled that:

-

There is no right under Canadian or international law for a province to unilaterally secede from Canada.

-

A clear majority on a clear referendum question would place an obligation on all parties — federal and provincial — to negotiate in good faith.

-

Any resulting separation would require a constitutional amendment, involving multiple levels of government and broad national consent.

So let’s be crystal clear:

-

A province can hold a referendum

-

A province can vote “yes” to secession

-

But it cannot leave Canada based on that vote alone

What Would Actually Be Required to Leave

A successful secession — even hypothetically — would require a constitutional amendment.

That means:

-

Approval from Parliament (House of Commons and Senate)

-

Agreement from at least seven provinces, representing at least 50% of Canada’s population — the so-called “7/50 Rule” under the Constitution Act, 1982

That’s not just Alberta saying yes. That’s most of the country saying yes.

In reality, the idea that Alberta — or any province — could “vote itself out of Canada” with a single ballot box exercise is a fantasy.

It’s a negotiated, constitutional, multilateral process that would take years (if not decades), and face enormous legal, political, and economic resistance at every step.

A Referendum Still Has Consequences

That doesn’t mean referendums are meaningless.

They can be politically powerful. Symbolically charged.

They can:

-

Apply pressure on Ottawa to take provincial concerns more seriously

-

Galvanize national attention around issues like electoral reform, representation, and autonomy

-

Serve as bargaining chips in constitutional discussions (though not guaranteed to succeed)

But what they cannot do — regardless of how emotionally charged or politically spun — is serve as a legal mechanism for separation.

So What’s the Real Function of a Separation Referendum?

It’s not a divorce.

It’s a loud, messy protest that forces the rest of the country to have a conversation.

And that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

If done with integrity and clarity — and not as a political stunt — a referendum can open doors to:

-

Reform discussions

-

Senate modernization

-

Electoral fairness

-

Resource jurisdiction agreements

-

Regional equity

But it needs to be rooted in facts, not fury.

Bottom Line

A referendum is not a trapdoor. It’s not a shortcut. It’s not a “get out of Confederation free” card.

At best, it’s an invitation to talk. At worst, it’s political theatre.

And anyone telling Albertans otherwise is either misinformed — or banking on your frustration to serve their agenda.

The Real Roadblock: Treaties, Indigenous Sovereignty, and the Constitution

The part of the separation debate no politician wants to talk about — but none of them can ignore.

You cannot talk seriously about Alberta separating from Canada without talking about Treaties 6, 7, and 8.

And yet, most political commentary about Alberta secession ignores them entirely — either out of ignorance or deliberate omission.

But here’s the truth:

Even if Alberta could find a legal and political path to separation, it cannot do so without Indigenous consent.

Why?

Because the land Alberta sits on is not “Alberta’s land.” It is treaty land — and those treaties are agreements between First Nations and the Crown in Canada, not with the Alberta government.

What Are Treaties 6, 7, and 8?

Between 1871 and 1900, the Crown signed several numbered treaties with First Nations across the prairies. These agreements — Treaty 6 (1876), Treaty 7 (1877), and Treaty 8 (1899) — cover virtually all of present-day Alberta.

These were:

-

Nation-to-nation agreements

-

Promises made by Canada, not the province

-

Signed under significant pressure and unequal conditions — but recognized as legally binding

They outlined:

-

Land-sharing agreements (not land surrender)

-

Rights to hunt, fish, and trap

-

Commitments to education, healthcare, and long-term protection

Most importantly, they represent ongoing constitutional obligations that Canada — and any entity acting within its framework — is bound to respect.

📜 Treaty 6

-

Government of Canada – Treaty Text

-

James Smith Cree Nation – Treaty 6 PDF

-

Treaty 6 History – Treaty Six Organization

📜 Treaty 7

-

Government of Canada – Treaty Text

-

Canadian Crown – Treaty 7 PDF

-

The Canadian Encyclopedia – Treaty 7 Overview

📜 Treaty 8

-

Government of Canada – Treaty Text

-

Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta – Treaty Articles

-

The Canadian Encyclopedia – Treaty 8 Overview

Section 35: Constitutional Protection of Treaty Rights

In 1982, the Constitution Act formally recognized and entrenched these agreements under Section 35, which states:

“The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

This makes treaty rights:

-

Legally binding under Canada’s highest law

-

Inalienable without Indigenous consent

-

Enforceable in court

So what does that mean for Alberta?

It means that any attempt to separate from Canada — or alter governance over treaty land — must include and obtain the consent of First Nations signatories.

And that’s not a suggestion. It’s a constitutional requirement.

The Legal and Moral Reality

If Alberta tried to separate:

-

Indigenous nations would have a legitimate legal claim to the land

-

They could assert sovereignty or remain part of Canada independently of Alberta

-

They could bring constitutional challenges to block Alberta’s attempt

-

International law would back them — and Canada would likely receive global support over Alberta in any dispute

In other words, Alberta does not “own” the land it occupies in the way many of its political leaders frame it. It is bound by law and treaty — and those obligations don’t go away with a referendum.

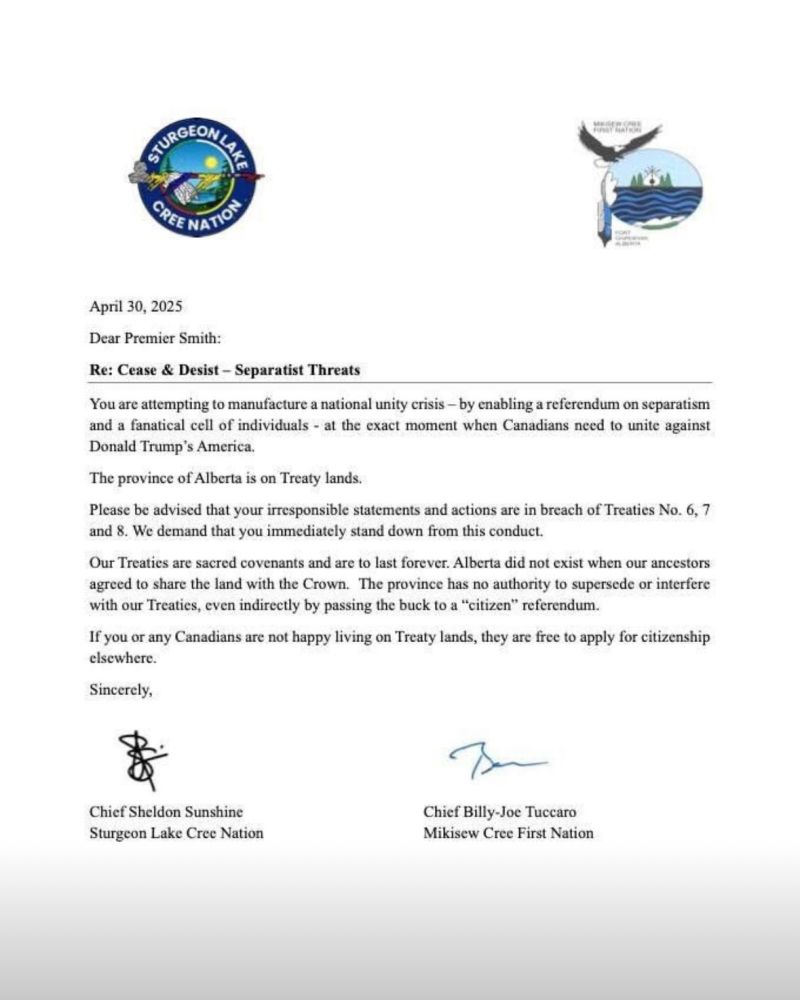

First Nations Are Already Speaking Out

Recently, leaders from Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation and Mikisew Cree First Nation wrote a letter to Premier Smith saying:

“Alberta is on Treaty lands. Your irresponsible statements and actions are in breach of Treaties No. 6, 7, and 8. We demand that you immediately stand down from this conduct.”

This wasn’t political posturing. It was a constitutional warning.

First Nations have:

-

Legal standing

-

Historical precedence

-

Constitutional protection

-

Moral authority

And any government that tries to ignore them is not only acting unlawfully — it’s acting without legitimacy.

Bottom Line

You can’t leave a country when you don’t control the land.

And Alberta doesn’t — not without First Nations’ consent.

Treaty land isn’t a footnote. It’s the foundation.

So unless Alberta plans to violate Section 35, ignore every legal precedent, and face a wall of Indigenous legal challenges and international condemnation — this discussion about secession ends here.

With a full stop.

And a legal brick wall that doesn’t move just because someone’s angry.

This Isn’t Quebec

Whenever talk of Alberta separating from Canada bubbles up, someone inevitably invokes the Quebec comparison:

“If Quebec has the right to separate, why can’t Alberta?”

It’s a fair-sounding question.

But like most soundbites, it falls apart under scrutiny.

Because the reality is: Alberta and Quebec are not constitutionally — or historically — the same. Not even close.

A Quick History Lesson: Quebec’s Path into Confederation

Quebec is one of Canada’s original founding provinces.

Before 1867, Quebec existed as the Province of Canada East, with its own government, civil code, legal traditions, and deeply rooted national identity — linguistically, religiously, and culturally.

When Confederation was negotiated in 1867, Quebec chose to join.

It negotiated terms, participated in constitutional conferences, and signed on under formal conditions that acknowledged its distinctiveness — including:

-

Protection of the French language

-

Preservation of the civil law system

-

Control over education and cultural matters

Quebec’s status as a founding nation within a nation has long been recognized, both politically and judicially.

It even has its own legal designation as a “distinct society”, affirmed in constitutional discussions and policies like the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords.

Legal and Political Standing

Even in the 1998 Supreme Court Reference on Quebec’s right to secede, the court was careful to emphasize Quebec’s unique constitutional status — not because it deserved special treatment, but because of its historical, cultural, and legal foundation.

No court has ever recognized Alberta as holding similar standing.

And there’s no legal or constitutional precedent that treats Alberta’s grievances — no matter how legitimate — as grounds for unilateral separation.

What It Means in Practice

-

Quebec can make the case that it has a distinct national identity with pre-Confederation roots.

-

Alberta cannot.

-

Quebec has had multiple referendums, backed by decades of legal and cultural infrastructure.

-

Alberta’s movement is comparatively recent, politically opportunistic, and lacks the constitutional foundation Quebec’s claim rests on.

Alberta? A Very Different Origin Story

As explained earlier, Alberta didn’t join Confederation.

It didn’t exist before it was created by federal statute in 1905.

It:

-

Wasn’t a colony

-

Had no self-governing structure

-

Had no standing legal or political identity

-

Did not negotiate terms of entry

-

Was carved from federal territory with its powers delegated to it

This isn’t a minor difference. It’s a foundational one.

Quebec came into Confederation through agreement.

Alberta came into being because of Confederation.

So when Quebec talks about sovereignty, it’s coming from a position of pre-existing nationhood.

When Alberta talks about sovereignty, it’s arguing from a place of post-Confederation creation.

That’s not semantics. That’s constitutional reality.

Alberta is a province. Quebec is a founding partner.

Alberta was created by Canada. Quebec helped create Canada.

They are not the same — and pretending they are only adds confusion to an already emotional issue.

So… Why Talk About It At All?

Because the anger is real. And ignoring it only makes it worse.

Let’s be honest:

Danielle Smith’s talk of Alberta separating from Canada didn’t come out of nowhere. It wasn’t born in a vacuum, and it didn’t happen because she had nothing else to talk about.

It’s tapping into something real — a deep and growing frustration among many Albertans (and other Western Canadians) who feel like they’ve been ignored, exploited, and politically dismissed by Ottawa for decades.

And if you’re from the Prairies, you don’t need a political scientist to tell you this.

You’ve lived it.

The Feeling Is Legitimate

Albertans are tired of:

-

Having their natural resource industries vilified while their taxes fund projects in provinces that oppose pipelines

-

Watching elections be decided before polls even close west of Thunder Bay

-

Seeing Ottawa make big promises during campaign season, only to ghost when it’s time to deliver

-

Feeling like no matter how they vote, the outcome is the same: power concentrated in central Canada

It’s no wonder people are angry.

It’s no wonder “separation” gets attention.

It’s no wonder someone like Danielle Smith would ride that sentiment to political traction.

But here’s the crucial part:

Just because the frustration is valid doesn’t mean the solution is.

Separation Is the Wrong Fix for the Right Problem

Separating from Canada won’t:

-

Magically solve the West’s underrepresentation in Parliament

-

Remove Indigenous treaty obligations

-

Guarantee economic stability

-

Or create a fairer democracy

In fact, it would likely:

-

Trigger constitutional chaos

-

Spark endless court battles

-

Violate treaty rights

-

Scare off investors

-

Split families, businesses, and institutions

-

And deepen the exact divide people are desperate to escape

It’s like blowing up your house because the roof leaks — only to realize you’re now living in the rubble.

What We Should Be Fighting For Instead

Because blowing it all up isn’t the answer — fixing it is.

Let’s call it like it is:

This system is broken.

-

The electoral map doesn’t reflect regional voices

-

The federal government’s power balance favours vote-rich provinces

-

National unity is fraying at the seams

-

Politicians exploit the divisions, not bridge them

But none of that gets fixed by walking away.

It gets fixed by staying and demanding more.

This Isn’t About Who’s in Power — It’s About How They Got It

This isn’t about Mark Carney.

It wasn’t about Justin Trudeau.

It wouldn’t magically improve under Pierre Poilievre or Jagmeet Singh.

Because the problem isn’t just leadership.

It’s structure.

We don’t need more political parties selling us the same system in a different colour.

We need to challenge the system itself — and build a new foundation that reflects all Canadians, not just the ones who live near a major media outlet.

So What Do We Actually Need?

Let’s make this real.

✅ 1. Electoral Reform

We need to stop pretending that first-past-the-post is “good enough.” It’s not.

It’s mathematically unfair, geographically biased, and politically manipulative.

It lets a party win 100% of the power with 35% of the vote — and leaves millions of Canadians functionally voiceless.

We need:

-

Proportional representation

-

Equal provincial seat distribution

-

Mechanisms to ensure regional voices can’t be ignored by urban population centers

✅ 2. Senate Reform

The Senate was supposed to balance regional interests. Instead, it’s a symbolic museum with limited power.

Reimagine it. Rebuild it. Let it do the job it was designed to do:

Protect the integrity of the federation — not just rubber-stamp federal agendas.

✅ 3. Resource Equity Agreements

No more treating Alberta like a cash machine and British Columbia like a transit corridor.

Each province contributes to this country — economically, culturally, and structurally.

We need:

-

National agreements that respect provincial jurisdictions

-

Revenue-sharing models that reflect actual contributions

-

Policy decisions that include the people most affected — especially rural and Indigenous communities

✅ 4. Local Power Without Losing National Identity

Alberta — and all provinces — should absolutely fight for more local autonomy in areas like:

-

Education

-

Healthcare delivery

-

Economic development

-

Land-use policy

But fighting for autonomy is not the same as fighting for separation.

We can demand local control without giving up on national unity.

✅ 5. Citizen-Driven Reform, Not Politician-Led Division

Change won’t come from those who benefit most from the status quo.

That means:

-

We need public pressure campaigns

-

We need referendums on electoral reform, not just separation

-

We need citizens showing up to forums, writing MPs, organizing, educating, voting smarter

-

We need to stop asking the people who profit from the rules to rewrite them for us

This won’t be solved by the next election.

But it starts right now — with us.